Update: Unfortunately this event has been cancelled.

On Tuesday, January 6 Balinese mask and shadow master I Gusti Putu Sidarta will perform at LPR with Shahzad Ismaily and members of Gamelan Dharma Swara and Gamelan Raga Kusuma. We caught up with Sidarta via email to ask him a few questions about Balinese mask dancing and shadow play. Thanks to Andrew McGraw at the University of Richmond for translating and providing a few clarifying notes (in italics). Check out the Q&A below.

LPR: You’ve been performing since you were a young child. How did you learn?

I Gusti Putu Sidarta: Beginning when I was a small child, I was already very familiar with the many kinds of Balinese ritual ceremonies that are based upon a syncretic Hindu-Buddhist faith. Almost everyday I heard the sound of the gamelan that was played in the temple during the (odalan) ceremony and also in the local meeting hall when our village group had rehearsals. I was very attracted to gamelan and whenever there was an empty seat I would try to sneak in. When I was in the third grade I started studying the gender wayang, which accompanies the wayang (shadow play). (McGraw: I should point out how unusual this is: this is considered the hardest Balinese music and it is very rare for young children to study it). My teachers were well respected artists from the villages of Bedulu and Tangkulak. After a year I could accompany the shadow play (McGraw: this is freakish!). Every evening I accompanied the shadow masters, and audiences started coming to see this little kid play “grown up” music. I then studied in the arts magnet high school, entering the theater department in order to become a shadow master myself, but I also studied dance and music seriously. This is when I began to study mask dancing seriously, because in Bali the movement, theatrical and vocal styles of the mask characters are similar to those in the shadow play. It was here that I also studied the very different styles of different Balinese villages. Eventually I graduated with a BA from the Indonesian Arts Institute (where I now teach). (McGraw: and a masters from the institute in Yogyakarta, Java).

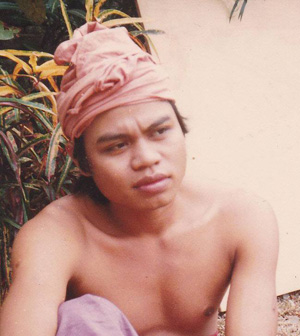

I Gusti Putu Sidarta performing with Gamelan Dharma Swara and Ni Kadek Dewi Aryani in 2010

For those who aren’t very familiar with Balinese shadow puppet and mask performance, could you describe the traditional role and duties of a dalang and topeng performer?

To become a dalang (McGraw: ‘shadow master’) and a topeng (McGraw: ‘mask’) dancer, one has to have a very strong and persistent interest and practical discipline. Like any other art, these can be studied from a purely technical standpoint, but to become a shadow master and a topeng dancer who is good/correct (McGraw: as in ‘truthful’) you must study for the entirety of your life. A shadow master and topeng dancer must master many kinds of art: music, dance, singing, many kinds of ancient texts in old, liturgical languages like Kawi which are the sources of the stories (Ramayana, Mahabharata, Babad and Tantri); you must master the principles of philosophy and religion and pursue the yogic spirituality through which one achieves personal clarity. Because of this the shadow master is considered a teacher of the people because through performance he gives moral guidance, what is appropriate and what is not, and critiques governmental politics, the behaviors of the populace. All that is erected through the dialogue of the clowns in the shadow play hides within its humor and entertainment these principles. According to the Dharma Pewayangan (McGraw: an ancient manuscript outlining the ways of the shadow master) there are many rules and formulations which must be followed by the dalang outside of his performance practice. He must master many mantra to protect himself from magic, he must learn the mantra to make holy water, and he must master the mantra to achieve taksu (McGraw: taksu means something like divine energy, performative charisma, sometimes similar to what a Christian might call a “grace.”) so that his performance has life, energy and connects to the audience.

What role does improvisation plays in wayang and topeng?

Traditional wayang and topeng have a standardized, but extremely flexible structure that allows the artist to adjust to any kind of place, time or context. Sections can be lengthened or shortened as needed, or even cut if needed. Because of this the performer really must know what is happening when and where he is performing. Sometimes because of local conditions humor is not appropriate. However, in any performance the “clowns” are the most important characters. In wayang these are Merdah, Malen, Sangut, Delem. These four guys determine the life and the success of the performance. Because through the clowns the dalang can freely improvise but in ways appropriate to local conditions and without disrupting the structure of the plot. Through the dialogue of these characters the dalang can deliver social criticism, advice on values, philosophy and religion and respond to current political issues. These dialogues are camouflaged in humor to the point that the audience may not realize they are philosophical and critical, and in this way we can avoid both boring or offending the audience.

How are the puppets and masks featured in wayang and topeng performances created?

The important thing for a dalang or topeng dancer is how to build the character and the plot or to keep the story flowing well so that the audience can clearly understand it. The dalang uses all elements of the arts to enliven his characters. For instance, to depict a refined and wise king, besides using the puppet for the mask which clearly illustrates this character, he will use a singing and vocal style, a movement and dance style, a speaking style which also depicts these characteristics. To illustrate the mood of a particular section of a story (sad, profound, calm, funny) we also use singing and narration and vocal techniques so that both the story and the characters come to life in the audience’s imagination.

Can you tell us about your collaboration with Shahzad Ismaily?

(McGraw: Shahzad has collaborated with Gusti both in Bali and NYC on previous occasions.)

We are going to try to create a new kind of theater based in the essence of wayang kulit and topeng which will represent a kind of ‘total theater’ that includes singing, narration, dialog, dance, acting and music. Music provides a space to express and improvise [a story] as a musical offering or as a theatrical performance, that gives color and feeling to theater. What is unusual here (McGraw: from a Balinese perspective) is that the theatrical aspect will involve a single person who will dance topeng, sing, narrate and perform shadow puppetry.

You’ve been involved in other experimental music and theater collaborations around the world. What inspired you to pursue such projects?

I’ve deeply enjoyed previous collaborations, although I am aware that every collaboration (music, dance or theater) always runs up against many obstacles and is almost never perfect. This is because every collaborator has his or her own strong ideas and ego. Here is the real opportunity for study. An opportunity to strive for understanding and valuing each other. In every collaboration all participants have rights and requirements to express themselves through opinion and concept. What must be stressed is the process of creation, not the end point or a “product.” Every process is accompanied by study, every collaborator studies how to give and receive, to value opinions, abilities and experiences of the others. The results of this process are the expansion of one’s own consciousness, consciousness of living together, consciousness of difference and uniqueness, beingness and nothingness, and the clarity of feeling. Spiritual experience is the joy and aim of my creativity.

Why did you choose the story of the reincarnation of Buddha as Sutasoma for your performance at LPR?

What is most needed now is for people to find peace within themselves so that they are not swept up by the flow of (modern) change. Because of this every person must go within themselves to become conscious of their true being. Sutasoma taught us to live consciously. The spirituality of this self-consciousness becomes the basis of one’s own thought, speech and act so that we are in harmony with our surroundings (McGraw: ‘nature’), respecting nature in all its being and upholding human values. Sutasoma is a symbol for raising one’s own (spiritual) consciousness.

How does a performance in a setting like Le Poisson Rouge differ from one in a more traditional, ceremonial context?

How does a performance in a setting like Le Poisson Rouge differ from one in a more traditional, ceremonial context?

In every performance, a traditional or a contemporary one, I, as a Balinese artist, always consider the: Place, Time, and Context of the performance. I always attempt to bring the essence of spirit of my tradition while I infuse it with the concepts and thinking of the moment (the now) as they are appropriate to the place, time and context.

Is there anything else people should know about your January 6 performance?

Come to the performance and (I hope) you will experience something of the consciousness raising Sutasoma models for us. I hope that the beauty of that message and of Balinese performing arts, as transformed by a collaboration in sound and movement will mean something to you.

posted by John